Financing a portion of consumption via borrowing, if managed soundly, helps boost individual and macroeconomic welfare. Financing offered by banks and financing companies enables people to buy real property and durable goods such as houses and vehicles that may otherwise be difficult to purchase at once with the existing level of wealth and income. On the other hand, close monitoring of borrowing dynamics and borrowing developments in Turkey, where consumption has a large share in GDP, is important for financial stability. Over-indebtedness may put a brake on household spending in times of economic slowdown and rising unemployment. Consequently, subdued demand reduces the corporate sector's revenues, leading to a further deceleration in economic activity. While default rates soar in household and corporate sectors, increased loan interest rates aggravate the burden on segments of the population that have borrowed at variable interest rates or that need to borrow again. Research shows that large-scale increases in household indebtedness before recession periods deepen the recession and impede the recovery process. Spending by households with a high level of indebtedness is relatively weak both during and after the recession (Harari, 2017). High indebtedness destabilizes spending, and a level of indebtedness above the general trend increases the risk of recession (Sutherland and Hoeller, 2012). Recessions occurring after substantial increases in household indebtedness tend to be more serious and long-lasting recessions (IMF, 2012). Although financial development supports economic growth in the long term (Levine, 1997, 1998; Beck and Levine, 2004), recent studies (Arcand et al., 2015; Sahay et al., 2015) reveal that there exists a threshold at which financial deepening stops having a positive effect on growth; when this threshold is exceeded, economic growth may decelerate. Since over-indebtedness of households increases vulnerabilities in the financial system and causes permanent damage in economies, it is crucial to define a set of "over-indebtedness" criteria and closely monitor them as well as to set an action framework to avoid negative effects of over-indebtedness.

This blog post seeks to explain the dynamics of household indebtedness, the ideal borrowing level, and the conditions under which an increase in household indebtedness can keep supporting financial stability.

The IMF study (2017) analyzing the impact of household indebtedness on long-term growth demonstrates that an increase in indebtedness which starts at low levels may ramp up economic growth in the long term as well. The contribution of a rise in indebtedness to long-term growth increases at a gradually slowing pace until the debt-to-GDP ratio reaches 36 percent. However, when this ratio exceeds 50 percent, the relationship between the debt ratio and long-term growth turns into an inverse correlation, i.e. an increase in debt reduces the long-term growth potential. On the other hand, the study by Lombardi et al. (2017) suggests that increased indebtedness accelerates growth in the short term through the consumption channel whereas it decelerates growth in the long term. This deceleration in the long term becomes visible when the debt ratio exceeds 60 percent and is even more pronounced at levels above 80 percent.

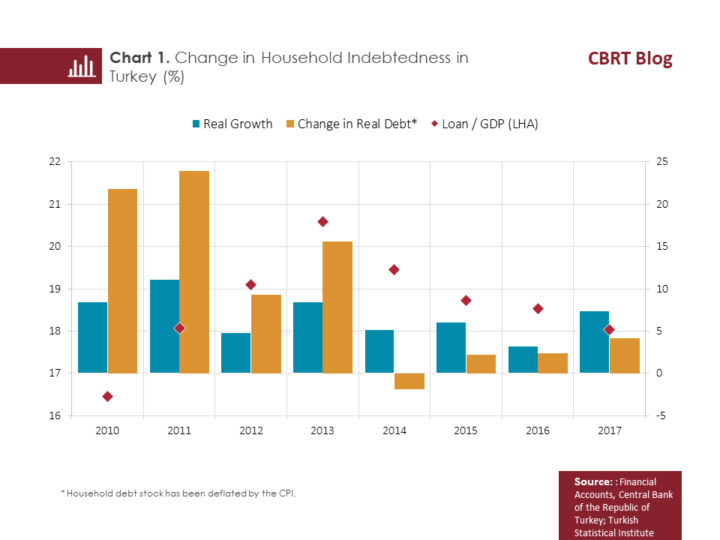

The household financial debt in Turkey, which corresponded to 2 percent of GDP as of 2002, reached 20 percent in 2013 and stabilized at 18 percent afterwards. Changes in household indebtedness in Turkey after the global crisis can be analyzed under two separate periods: the period of strong increases until 2014, and the post-2014 period of relatively weaker increases during which outcomes of macroprudential policies to prevent excessive borrowing by consumers have become visible (CBRT, 2014) (Chart 1).

The decline in the ratio of households' liabilities to assets in Turkey continued from 2013 through 2017. In a period of increased geopolitical uncertainties and exchange rate volatility, FX borrowing has become an important issue in terms of financial stability in emerging market economies (EMEs). As households cannot borrow at variable interest rates (except for housing loans) or get FX loans pursuant to regulations in effect, they do not bear any exchange rate or interest rate risk.

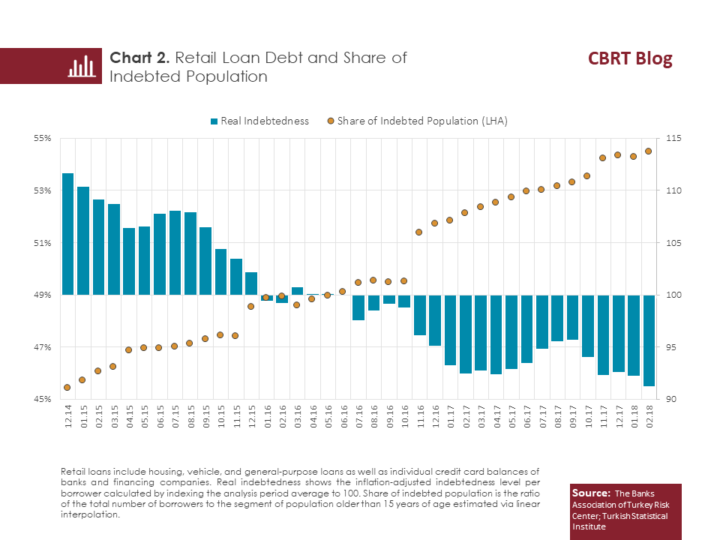

The ratio of retail loan borrowers to the segment of population older than 15 years of age[1] rose to 54 percent from 45 percent in the post-2014 period while the real debt per borrower has remained below the average of the periods analyzed since the second half of 2016 (Chart 2).

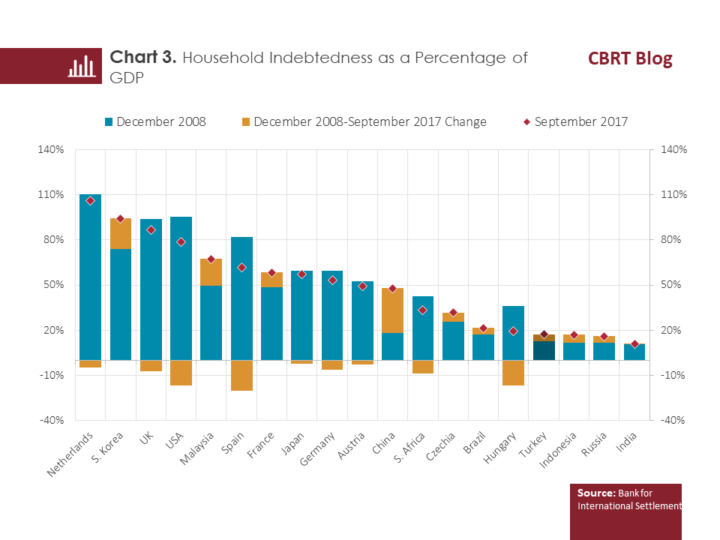

Although it may not be an accurate approach to take the borrowing limits calculated in the studies by the IMF (2017) and Lombardi et al. (2017) as universally ideal limits, we can say that household indebtedness in Turkey standing at 18 percent is low. In fact, household indebtedness in Turkey is higher than in some EMEs such as Indonesia, Russia, and India but it is lower than household indebtedness in a significant number of advanced economies (Chart 3).

On the other hand, the IMF study (2017) associates the capacity of household indebtedness to support financial stability with the presence of certain factors that provide resilience against financial shocks. In outward-oriented countries with a fixed exchange rate system where macroprudential policies are not implemented, transparent financial regulations are lacking, follow-up legislation is insufficient, and the inequality in income distribution is high, the threshold limit may be below the defined average.

Angeles (2015) points out that financial crises around the world arise from increases in retail loans rather than in corporate loans and that household borrowing should be managed in a controlled manner.

Household credit risk outlook in Turkey has improved due to maturity and installment caps on consumer loans and individual credit cards (ICC) as well as restriction of vehicle and housing loan utilization based on asset value, and restriction of ICC borrowing based on income. In periods of extensive non-accommodative macroprudential policies, the credit risk outlook remained unimpaired while the shift to a more prudent structure in household indebtedness has been completed without a significant problem. It is believed that supporting this framework with parameters such as the ratio of total indebtedness and debt service to periodic income in the upcoming period will further increase resilience.

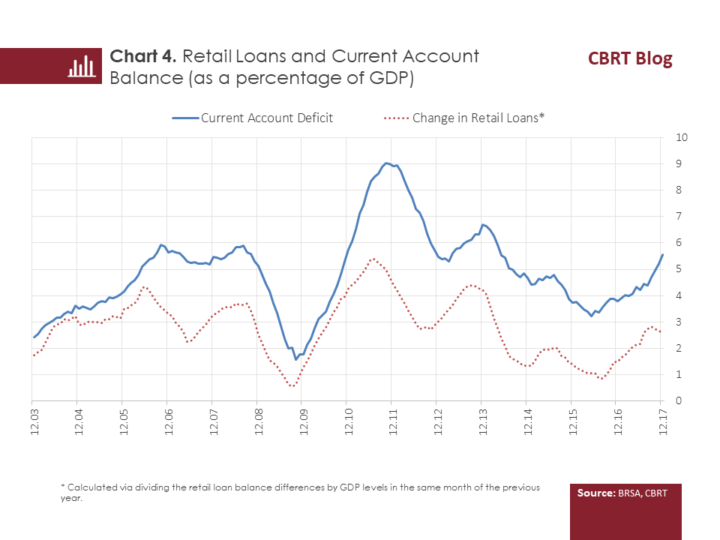

Because of the persistently high level of structural current account deficit in Turkey, the macrofinancial dimension of consumer loans should also be taken into account. There is a strong relationship between retail loan growth and current account balance (Chart 4). Keeping the current account deficit at more reasonable levels by achieving price stability and financial stability is among the primary objectives for the Turkish economy. It is projected that an increase in the propensity to save as well as in household indebtedness in the short and medium term will also produce positive outcomes in the long term.

To sum up, household indebtedness in Turkey is lower than in peer countries. However, it is of critical importance for a balanced growth that factors such as the propensity to save, financial stability, current account balance, and changes in the general price level are taken into account when managing this process.

To sum up, household indebtedness in Turkey is lower than in peer countries. However, it is of critical importance for a balanced growth that factors such as the propensity to save, financial stability, current account balance, and changes in the general price level are taken into account when managing this process.

[1] As of end-2017, there were approximately 25 million individual credit card (ICC) holders, which corresponds to 44 percent of the segment of population older than 15 years of age.

Bibliography

Angeles, L. (2015). “Credit Expansion and the Economy.” Applied Economics Letters 22 (13): 1064–72.

Arcand, J. L., Enrico B. ve Ugo P. (2015). “Too Much Finance?” Journal of Economic Growth 20 (2): 105–48.

Beck, T. ve Ross L. (2004). “Stock Markets, Banks, and Growth: Panel Evidence.” Journal of Banking and Finance 28 (3): 423–42.

Harari, D. (2017). Household debt: statistics and impact on economy, House of Commons Library, Briefing Paper Number 7584.

IMF. (2012). “Dealing with household debt”, Chapter 3, World Economic Outlook, April 2012

IMF. (2017). Household Debt and Financial Stability. Global Financial Stability Report October 2017: Is Growth at Risk?

Levine, R. (1997). “Financial development and economic growth: Views and agenda.” Journal of Economic Literature 35 (2): 688–726.

Levine, R. (1998). “The Legal Environment, Banks, and Long-Run Economic Growth.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 30 (3): 596–613.

Lombardi, M. J., Mohanty, M. ve Shim, I. (2017). “The Real Effects of Household Debt in the Short and Long Run.” BIS Working Paper 607, Bank for International Settlements, Basel.

Sahay, Ratna, Martin Čihák, Papa N’Diaye, Adolfo Barajas, Ran Bi, Diana Ayala, Yuan Gao, Annette Kyobe, Lam Nguyen, Christian Saborowski, Katsiaryna Svirydenka ve Seyed Reza Yousefi. (2015). “Rethinking Financial Deepening: Stability and Growth in Emerging Markets.” IMF Staff Discussion Note 15/08, International Monetary Fund, Washington DC.

Sutherland, D. ve Hoeller, P. (2012). "Debt and Macroeconomic Stability: An Overview of the Literature and Some Empirics", OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1006, OECD Publishing, Paris

CBRT. (2014). “Impact Analysis of Macroprudential Measures Targeted on Consumer Credits in Turkey”. Financial Stability Report, Volume: 19